Causes of Generic Drug Shortages: Manufacturing and Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

Jan, 28 2026

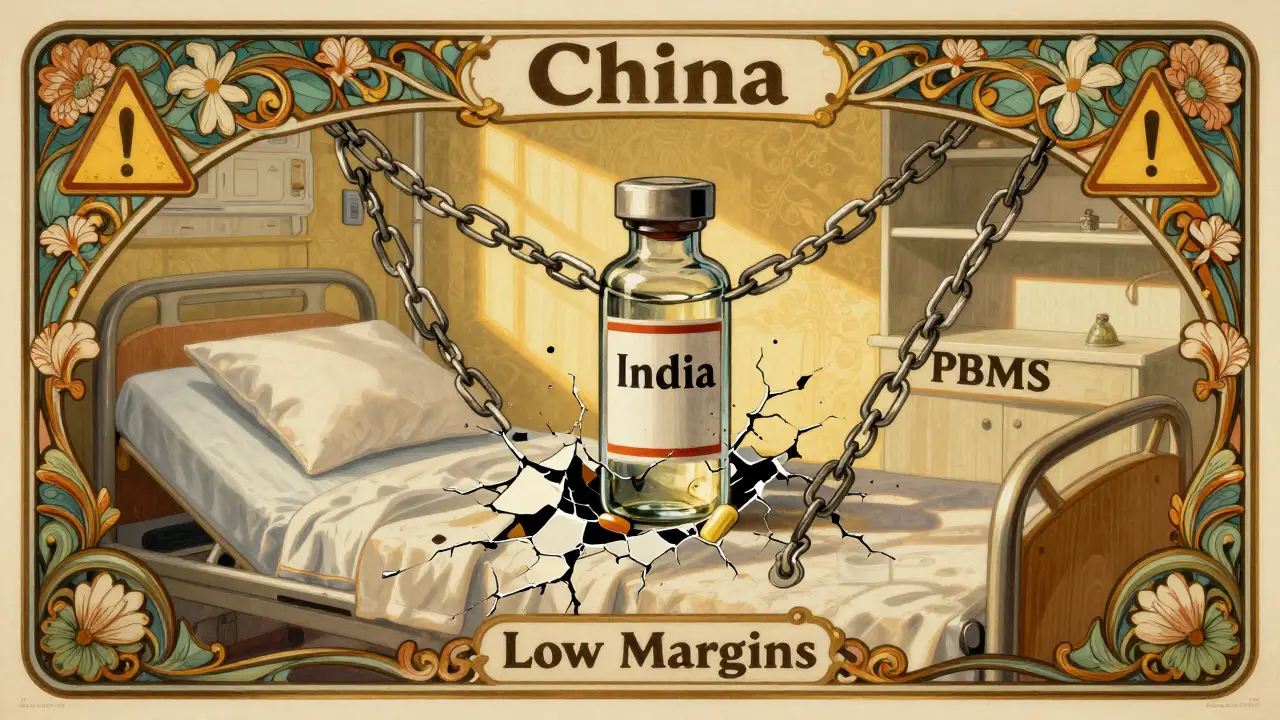

Every year, thousands of patients in the U.S. face delays or disruptions in their treatment because a simple, life-saving generic drug isn’t available. It might be an antibiotic, a chemotherapy agent, or even an anesthetic used during surgery. These aren’t rare exceptions-they’re routine occurrences. And the root of the problem isn’t a single bad batch or a bad actor. It’s a broken system built on low profits, global dependencies, and zero room for error.

Manufacturing Problems Are the #1 Cause

More than 60% of all drug shortages in the U.S. come down to one thing: manufacturing failures. This isn’t about occasional glitches. It’s about entire production lines shutting down because of contamination, equipment breakdowns, or FDA violations. One cleanroom gets mold in it? Production halts. A single valve fails in a sterile injectable line? That drug disappears from shelves for months.

Generic drug makers operate on razor-thin margins. Unlike branded drugs that can charge hundreds or thousands of dollars per dose, generics often sell for pennies. A typical generic antibiotic might cost $0.10 per pill. After distribution, pharmacy fees, and PBM markups, the manufacturer might see less than 5% profit. That doesn’t leave much room for investing in modern equipment, backup systems, or quality control teams. So when something breaks, there’s no spare capacity to pick up the slack.

The FDA has documented over 100 manufacturing inspections resulting in warning letters or import alerts in the past five years-many tied to generic injectables. These aren’t small issues. A single violation can shut down a facility for over a year while the company scrambles to fix it. And because so many drugs are made in the same few plants, one shutdown can ripple across the entire supply chain.

Global Supply Chains Are a Single Point of Failure

Eighty percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in U.S. generic drugs come from just two countries: China and India. That’s not diversification-that’s concentration. And it’s dangerous.

When a flood hit a major API plant in India in 2020, or when a Chinese factory was locked down during COVID-19, the U.S. felt it immediately. There were no alternatives. No backups. No local suppliers stepping in. These countries aren’t just suppliers-they’re the backbone of the entire system. And they’re not regulated the same way the U.S. is. Quality standards vary. Inspections are infrequent. And when problems arise, there’s no quick fix.

Even worse, many of these foreign manufacturers serve multiple clients. One plant might produce the API for five different generic versions of the same drug. If that plant goes offline, all five drugs vanish at once. And because these facilities are often owned by large conglomerates, decisions about which drugs to prioritize are made based on profit-not patient need.

No Buffer, No Backup, No Safety Net

Branded drug companies keep extra stock. They plan for demand spikes. They have safety stocks. Generic manufacturers? They don’t. They run lean-sometimes running at 98% capacity. That’s efficient on paper. In reality, it’s a disaster waiting to happen.

Why? Because margins are so low, there’s no financial incentive to overproduce. Why make 10% more pills if you’re barely breaking even on the 90% you’re already selling? This is called “just-in-time” manufacturing. It works great when everything runs smoothly. When a single supplier fails, the whole chain collapses.

There’s also no redundancy in production. A single company might be the only one making a specific generic drug. If that company shuts down, exits the market, or gets acquired, that drug disappears. Since 2010, over 3,000 generic products have been discontinued. Many were low-margin drugs that no one wanted to make anymore-not because they weren’t needed, but because they didn’t pay enough.

Market Forces Are Pushing Manufacturers Out

It’s not just about bad manufacturing. It’s about bad economics.

Three pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) control about 85% of U.S. prescription drug spending. These companies negotiate prices with manufacturers on behalf of insurers. To win contracts, generic drug makers have to slash prices further and further. Some drugs now sell for less than the cost of packaging. When a drug’s price drops below the cost of production, manufacturers stop making it. And once they exit, it’s nearly impossible to get back in. The FDA requires re-inspection, re-certification, and re-validation-costs that can run into millions. No one’s going to pay that unless they’re sure they’ll get paid back.

Even when a drug is in shortage, PBMs often don’t prioritize getting it back on formularies. They push alternatives-even if those alternatives are more expensive, less effective, or not approved for the same use. Hospitals end up scrambling to find substitutes, sometimes using drugs off-label, delaying treatments, or rationing doses.

Why Canada Handles This Better

Canada faces the same global supply chain issues. The same API factories. The same low margins. But they have fewer shortages. Why?

Because Canada treats drug supply as a public health issue-not a market competition. They have a national stockpile for essential medicines. They coordinate between manufacturers, hospitals, regulators, and pharmacists. When a shortage hits, they don’t wait for the market to fix itself-they act.

The U.S. stockpile? It’s only for bioterrorism or natural disasters. Not for a shortage of insulin or sodium bicarbonate. There’s no national plan to monitor inventory levels, forecast demand, or incentivize production of low-margin drugs. Meanwhile, Canadian regulators work with manufacturers to keep production going-even if it means paying a little more to keep a critical drug in stock.

What’s Being Done-And Why It’s Not Enough

There are proposals. The RAPID Reserve Act, introduced in 2023, aims to create a strategic reserve of critical generic drugs and offer tax incentives for domestic manufacturing. The FTC is investigating PBMs for anti-competitive behavior. The AMA is pushing to stop formulary exclusions that worsen shortages.

But these are band-aids. The real problem? The system rewards cutting costs over building resilience. The moment a manufacturer invests in backup equipment, expands capacity, or builds a second source for APIs, they’re spending money on something that doesn’t directly increase their profit. In a market where every penny counts, that’s a risk no one wants to take.

Until we change the rules-until we pay for the actual cost of making essential medicines, not just the lowest possible bid-we’ll keep seeing the same shortages. The same delays. The same patients caught in the middle.

Patients Are Paying the Price

Behind every shortage statistic is a person. A cancer patient waiting for their chemo. A diabetic running out of insulin. A child with an infection who can’t get antibiotics. Hospital pharmacists now spend 50-75% more time managing shortages than they did a decade ago. Some spend hours calling other hospitals, trying to borrow vials. Others have to use less effective, more toxic alternatives.

And here’s the worst part: in one out of every four shortage reports, no reason is given at all. No explanation. No timeline. Just silence.

Generic drugs make up 95% of all drug shortages in the U.S. and Canada. They’re the backbone of affordable care. But the system that keeps them cheap is the same one that makes them disappear when we need them most.

The fix isn’t complicated. We need to stop pretending that drugs are just another commodity. We need to pay for quality. We need to incentivize redundancy. We need to build domestic capacity. And we need to treat access to essential medicines as a right-not a market outcome.

Until then, the shortages will keep coming.